Shortly before the Parliamentary recess, on 25 July 2020, the Government made a much anticipated, announcement that it would be introducing legislation modifying the formality requirements of s. 9 of the Wills Act 1837 so as to expressly permit the remote witnessing of wills via the use of video-conferencing technology.

The issue of making wills has had a lot of attention since the pandemic started. There has been a huge surge in people making wills and the social distancing measures have created problems for people in terms of complying with the witnessing requirements of s. 9 of the Wills Act.

In the lead up to the announcement, there has been considerable debate over the issue of whether or not remote witnessing of wills was already permitted under the existing law, as covered in my earlier posts on this topic.

The answer to the question of whether or not the requirement of “presence” for the purposes of the witnessing requirements of s. 9 of the Wills Act 1837 already extended to remote presence is not clear cut. Many practitioners have taken the view (as has the Law Society) that wills must be witnessed in person in the traditional way. Others have taken a bolder approach and (whilst no doubt advising clients carefully about the risk that a remotely witnessed will may not be upheld) have participated in the remote execution of wills.

Legislation expressly authorising remote witnessing has been implemented (at a much earlier stage of the pandemic) in a number of English speaking jurisdictions around the world, including New York, Ontario, New Zealand and Australia.

As at the date of the Government’s announcement, no draft legislation had been produced. However, guidance was published by the Ministry of Justice and, in consultation with the Ministry of Justice, by a committee of the Society of Trusts and Estate’s Practitioners, in which I participated.

The MOJ guidance can be located here

The STEP guidance can be located here

At the time of the Government announcement, the lockdown rules had been relaxed, Covid-19 case numbers had dropped dramatically and the impediments to making a traditionally executed will had diminished. However, it is clear that Covid-19 has not gone away and, in a week where case counts are rising and restrictions on social contact are being brought back in, the need for this reform appears more pressing.

The Wills Act 1837 (Electronic Communications) (Amendment) (Coronavirus) Order

The Statutory Instrument to bring into law this change was laid before Parliament this week on 07 September 2020. It may come as a surprise to some that a change to the Wills Act has been brought about by Statutory Instrument. However, the change is made pursuant to s. 8 of the Electronic Communications Act 2000, which creates the power to modify other Acts so as to authorise the use of electronic communications for a wide variety of purposes, including anything that requires a witness (s.8(2)(c)).

The material provisions of the Order provide as follows:

“Amendment of the Wills Act 1837

2.—(1) Section 9 of the Wills Act 1837(b) is amended as follows. (2) The existing text becomes subsection (1).

(3) After that subsection, insert—

“(2) For the purposes of paragraphs (c) and (d) of subsection (1), in relation to wills made on or after 31 January 2020 and on or before 31 January 2022, “presence” includes presence by means of videoconference or other visual transmission.”.

Saving Provision

3. Nothing in this Order affects—

(a) any grant of probate made; or

(b) anything done pursuant to a grant of probate, prior to this Order coming into force.”

Guidance on Remote Witnessing

The Ministry of Justice Guidance explains the process of remote execution, as follows:

Signing and witnessing a will by video-link

Signing and witnessing by video-link should follow a process such as this:

Stage 1:

- The person making the will ensures that their two witnesses can see them, each other and their actions.

- The will maker or the witnesses should ask for the making of the will to be recorded

- The will maker should hold the front page of the will document up to the camera to show the witnesses, and then to turn to the page they will be signing and hold this up as well.

- By law, the witnesses must see the will-maker (or someone signing at their direction, on their behalf) signing the will. Before signing, the will-maker should ensure that the witnesses can see them actually writing their signature on the will, not just their head and shoulders.

- If the witnesses do not know the person making the will they should ask for confirmation of the person’s identity – such as a passport or driving licence.

Stage 2:

The witnesses should confirm that they can see, hear (unless they have a hearing impairment), acknowledge and understand their role in witnessing the signing of a legal document. Ideally, they should be physically present with each other but if this is not possible, they must be present at the same time by way of a two or three-way video-link.

Stage 3:

- The will document should then be taken to the two witnesses for them to sign, ideally within 24 hours. It must be the same document.

- A longer period of time between the will-maker and witnesses signing the will may be unavoidable (for example if the document has to be posted) but it should be borne in mind that the longer this process takes the greater the potential for problems to arise.

- A will is fully validated only when testators (or someone at their direction) and both witnesses have signed it and either been witnessed signing it or have acknowledged their signature to the testator. This means there is a risk that if the will-maker dies before the full process has taken place the partly completed will is not legally effective.

Stage 4:

The next stage is for the two witnesses to sign the will document – this will normally involve the person who has made the will seeing both the witnesses sign and acknowledge they have seen them sign.

- Both parties (the witness and the will maker) must be able to see and understand what is happening.

- The witnesses should hold up the will to the will maker to show them that they are signing it and should then sign it (again the will maker should see them writing their names, not just see their heads and shoulders).

- Alternatively, the witness should hold up the signed will so that the will maker can clearly see the signature and confirm to the will maker that it is their signature. They may wish to reiterate their intention, for example saying: “this is my signature, intended to give effect to my intention to make this will”.

- This session should be recorded if possible.

Stage 5:

-

If the two witnesses are not physically present with each other when they sign then step 4 will need to take place twice, in both cases ensuring that the will maker and the other witness can clearly see and follow what is happening. While it is not a legal requirement for the two witnesses to sign in the presence of each other, it is good practice.

Key points to note for those attempting remote execution:

- Beyond permitting the use of videoconferencing technology for the purposes of the witnessing requirements of the Wills Act 1837, the legislation makes no other changes to the substantive law relating to the making of a valid will.

- The legislation authorises the use of video conferencing technology only for the purposes of the witnessing requirements of the Wills Act. This change in the law does not expressly allow a testator to direct a person to sign the will on their behalf in the testator’s remote presence, pursuant to what will become s.9(1)(a) of the Wills Act once the Order comes into force. Readers who have been following this debate closely will be aware that some practitioners had been using this method during lockdown to allow the will to be executed remotely in a single video call, so as to avoid the need for the will to travel backwards and forwards between testator and witnesses, by having the testator direct the practitioner to sign the will over the video conference, with the practitioner’s signature then being witnessed by persons in the room with the practitioner. This practice is not expressly authorised under the new legislation.

- As is evident from the Ministry of Justice guidance, above, the remotely executed will will be very well traveled by the end of the process. The Ministry of Justice decided not to adopt the New Zealand approach, which permits the participants to sign counterpart wills. The complete original will must be sent back and forth between the testator and the witnesses. There is obviously scope for the document to go astray if the will is being sent in the post and the introduction of delay carries with it risk, particularly in the case of an elderly or ill testator. I would speculate that this change in the law may transpire to be more popular with younger testators, comfortable with using technology, than it will be with the elderly testators most vulnerable to Covid-19.

- Testators will need to be advised to choose their witnesses with care. Normally, with in person execution, a witness will have limited opportunity to read through the content of the testator’s will and will often see nothing other than the final page where the attestation clause is. There is a loss of confidentiality in a will that has been posted to the witnesses. The witnesses must be trusted and entirely independent – imagine the problems caused by a witness who has a connection to a disinherited beneficiary, who might be tempted to persuade the testator to change their mind or might refuse to witness the will when they receive it, or by a loose-lipped witness who tells other parties about the contents of the will.

- It is critical that all participants have a clear line of sight. That is far less of an issue when a will is executed in the traditional way and the law on the conventional attestation process confirms that a participant must either see or have an opportunity to see the act of signature, which will suffice even if they did not in fact watch the signing of the will. With remote witnessing, there is no opportunity to see the act unless it takes place on screen. Some thought needs to be given to the logistics of signing on screen, it may not be possible for a fixed webcam to be moved so as to enable the participants to see the act of signing. Those of us regularly using technology such as Zoom and Skype will have experienced laggy connections and screen freeze during video chats. If the act of signing is not visually witnessed by all participants for any reason, the signing party will need to acknowledge their signature by holding it up to the camera.

- STEP and the MOJ both advise that the process should be recorded and the recording retained. I would recommend that practitioners who are planning to adopt remote witnessing have a test run of the process using the platform that they are planning to use with clients, so as to iron out any wrinkles in the process. Practitioners will also need to agree with clients who will be responsible for storing any recording.

- Extra care will be required where remote witnessing is adopted, not only to ensure the formality requirements are complied with, but also to ensure that steps are taking to mitigate the risk of undue influence or fraud. It is harder to guard against such risks when you are not meeting the client in person. I strongly recommend that readers take a look at the STEP briefing note which offers further guidance around these issues.

- It would be sensible to amend attestation clauses to reflect the manner in which the will has been witnessed, if remote witnessing is adopted.

Retrospective Effect

Note that the legislation is of retrospective effect, applying to wills made on or after 31 January 2020, when the first confirmed case of Covid-19 was recorded in the UK and, unless extended, it has a sunset clause providing for it to cease to apply after 31 January 2022.

The guidance published by the MOJ in July identified two exceptions to the proposed retrospective effect of the legislation:

“The legislation will apply to wills made since 31 January 2020, the date of the first registered Covid-19 case in England and Wales, except:

- cases where a Grant of Probate has already been issued in respect of the deceased person

- the application is already in the process of being administered”

The proposed exception for applications for a grant “already in the process of being administered” did not make it into the Order – probably due to the difficulty of defining what was meant by being in the process of being administered and perhaps also due to concern that unfairness might be caused by a race to get an application for a grant in before the announced change to the law came into effect.

The saving provision as enacted in the Order provides that the legislation does not apply to grants of probate issued before the Statutory Instrument was made, nor does it affect anything done pursuant to a grant of probate issued prior to the legislation coming into force. This appears intended to have the effect that any will that has already been admitted to probate will be unimpeachable, even if there had been an attempt to make a later remotely witnessed will on or after 31 January 2020. Conversely, seemingly, grants of letters of administration on intestacy which have already been issued can be impeached, however, where there is a remotely witnessed will made valid by this retrospective change in the law.

The rational behind this distinction appears to be that testamentary intentions should be allowed to prevail over an intestacy. It is likely that there will be very few estates, affected by the saving provision. Nonetheless, this carve out could lead to some tough cases. As Juliet Brook, Principal Lecturer at Portmouth Law School, comments on Twitter: “sometimes previously expressed testamentary wishes can be much further from the testator’s revised testamentary wishes than an intestacy distribution – particularly if the testator’s family circumstances have changed significantly”.

The justification for the differential treatment most likely lies in the recognition that there is a need to strike a compromise between upholding testamentary intentions, where possible, and the potential upheaval caused by retrospective legislation.

Paragraph 3.(b) of the saving provision, providing that nothing done pursuant to a grant of probate will be effected by the Order, is curious. If 3.(a) already has the effect of precluding a grant of probate of an earlier traditionally executed will from being revoked on the grounds that there was a later attempt to make a remotely witnessed will prior to the coming into force of the the Order, why is 3.(b) required? Possibly, this is a slip in language and the intention at 3.(b) is to refer more broadly to grants of representation, including grants of letters of administration, so that personal representatives, and those understood to be the beneficiaries of the estate before this change in the law, do not find themselves in difficulties where the estate has been distributed. If this provision is construed as covering grants of representation, beneficiaries on intestacy who have already received a distribution from the estate would not be required to refund it, even if the grant of letters of administration is now set aside and the remotely witnessed will admitted to probate on the basis of this retrospective change in the law. If it is not construed as covering any actions already taken pursuant to a grant of letters of administration, beneficiaries who have already received a distribution under a grant of letters of administration subsequently set aside on the grounds that there is a remotely witnessed will retrospectively made valid by the Order, may be liable to refund their legacies. See Re Diplock [1948] Ch. 465 (CA) for the sorts of difficult considerations that arise in such circumstances in assessing whether or not there should be a liability to refund.

A further wrinkle in the drafting is that no thought appears to have been given to the situation where letters of administration with the will annexed have already been issued (where for example the named executors in the will had pre-deceased or were unwilling or unable to take the grant) but there is a later remotely witnessed will made after 31 January 2020. If a grant of probate had been issued in relation to the earlier, traditionally made will, this would not be affected by the change in the law and, seemingly, cannot now be revoked. It appears unlikely that it is intended that LOA with the will annexed could be revoked on the grounds of a later remotely witnessed will made between 31 January 2020 and the coming into force of these provisions, where a grant of probate in relation to that earlier will could not be revoked. This again appears to be a slip of terminology, given that it is clear from the explanatory memorandum that the intention was to make a distinction between cases where there has been an attempted remote will on or after 31 January 2020, but before this Order comes into effect, and an earlier will has already been admitted to probate, as contrasted with situations where a grant of letters of administration on intestacy has already been obtained on the assumption the attempted remote will was not valid. Most likely, a purposive approach would be taken to the interpretation of “grants of probate” so as to include letters of administration with the will annexed within the saving provision.

Of course, there are credible arguments that remote witnessing was already permitted under s. 9 of the Wills Act 1837 before this reform, as discussed in my earlier posts on this topic. It would be open to an intended beneficiary under an attempted remotely witnessed will, unable to avail themselves of the provisions of s.9(2) of the Wills Act, as amended by the Order, to seek to argue that the remotely witnessed will was compliant with the existing law in any event.

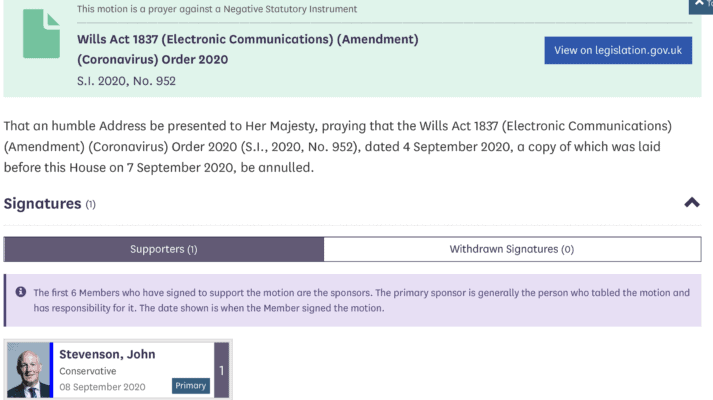

Whilst the legislation has been tabled, and is due to come into force 21 days after being laid before Parliament, it is not yet law. Barbara Rich, barrister of 5 Stone Buildings, has described the unusual manner in which this legislation has come about, in her blog post on Medium here, as reminiscent of the Cheshire Cat. Guidance preceding the legislation, or even the publication of the draft legislation, in much the same way as the Cheshire Cat’s grin preceded the rest of him. Of interest, there has been an Early Day Motion, by John Stevenson MP, to annul the Statutory Instrument – a potential (Cheshire) cat amongst the pigeons in circumstances where testators may already have relied upon the guidance issued by the Government. The basis for Mr Stevenson’s objection is not known, however he was in practice as a solicitor and may have concerns about the risk of fraud or undue influence presented by dispensing with in person attestation.

Helpfully, Cambridge academic, Brian Sloan, has pointed out on Twitter that the last time the House of Commons annulled a negative statutory instrument was in 1979, so it appears unlikely that the statutory instrument will be derailed on this basis.

However, the retrospective effect of the legislation may provide scope for a challenge to the validity of the legislation on the grounds that it is ultra vires, on the basis that goes further than secondary legislation made pursuant to s.8 of the Electronic Communications Act is permitted to go, or on the basis of a human rights argument. I certainly would not hold myself out as a constitutional lawyer, and would be very interested in anyone has any views on this point.

Generally, the principle is that where secondary legislation has a substantive effect on rights, rather than a change of a merely procedural character, there must be a clear provision in the enabling legislation conferring the power to make retrospective delegated legislation. It is not a requirement that there be an express provision, merely that there is a sufficiently clear provision enabling retrospective effect: R (Christchurch Borough Council) v Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government [2019] PTSR 598.

Assuming that the premise of the Order (as set out in the explanatory memorandum) is correct and remote witnessing was not permitted under the existing law, the change appears to me to be one with substantive rather than merely procedural effect, in so far as it has the effect of making valid an attempted will that otherwise would fail for lack of compliance with the formality of requirements of s. 9 of the Wills Act, prior to this change in the law, with the result that anyone entitled on intestacy or an earlier traditionally executed will not yet admitted to probate will lose their entitlements.

Section 8 of the Electronic Communications Act 2000 gives sweeping powers to the “the appropriate Minister” to allow the use of electronic communications for a wide array of purposes, however there is no obvious express provision enabling retrospective effect.

Possibly the answer lies in s. 9(6) of the Electronic Communications Act which provides, in relation to orders made pursuant to s. 8, that:

“The provision made by such an order may include—

(a)different provision for different cases;

(b)such exceptions and exclusions as the person making the order may think fit; and

(c)any such incidental, supplemental, consequential and transitional provision as he may think fit…”

The language of s.8 of the Electronic Communications Act all appears prospective in nature – secondary legislation can be made for the purposes of authorising or facilitating the use of electronic communications for the “doing” of specified acts. However, it may be argued that the ability to include different provision for “different cases” (suggesting differential treatment of individual instances of particular activities) can be deemed to be a sufficiently clear provision to enable the Order to be made with retrospective effect in relation to certain cases where there has been an attempt to use electronic communications for one of the purposes covered by s.8 of the Electronic Communications Act, prior to the enactment of a statutory instrument expressly permitting such acts. A similar argument appears to have prevailed in the Christchurch case.

If the Order does offend the retrospectively rule, it is only likely to be the retrospective element of the Order that would be vulnerable to being found to be ultra vires. However, this could conceivably provide an argument that disaffected beneficiaries, who are affected by a remote will made between 31 January 2020 and the coming into force of the change in the law, could deploy in order to argue that the retrospective provisions are of no effect.

Human rights considerations, in particular Protocol 1 Art 1. of the ECHR (right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions), may also be engaged in some cases. An expectant beneficiary has nothing until the point of death and the mere expectation of an inheritance has been held not to constitute a possession for the purposes of Protocol 1 Art.1: Marckxx v Belgium (1979) 2 EHRR 330. It is unlikely therefore that the human rights of any expectant beneficiary under an earlier traditionally executed will or on intestacy will be considered to have been breached by the retrospective validation of an attempted remote will, in any case where the remote will-maker has not yet died. However, the Protocol 1 Art. 1 rights of any beneficiary under an earlier traditionally executed will or intestacy who loses their rights as a result of this change in the law, where a remotely executed will has been made retrospectively valid after the death of the testator and after the beneficiary’s rights have crystallised, do appear to be affected by this change in the law and this may also provide a basis for challenge.

What Does the Future Hold for Will Reform?

I would speculate that remote witnessing is here to stay and that the Order will eventually be extended to become a permanent change to the law of wills. Further reform is also on the agenda. Nick Hopkins, Law Commissioner for Property, Family and Trust Law, attended the Society of Legal Scholars Annual Conference last week and is reported (thanks to Brian Sloan) to have confirmed that there is a clear commitment from the Commission and the MOJ to progress the will reform project. I have written here, with Juliet Brook, about the Law Commission recommendations concerning will reform and the possibility of a statutory dispensing power being introduced, to allow informal testamentary intentions to be upheld.

Thanks

A note of thanks to everyone who has participated in a lively debate on Twitter over the issues covered in this blog post – in particular Brian Sloan, Barbara Rich, Juliet Brook, Alexander Learmonth and Levins Solicitors.